KUALA LUMPUR, Dec 9 – An open and transparent parliamentary enquiry into the more than two-decade delay on the construction of Hospital Lawas in Sarawak were among the many recommendations made at the conclusion of the recently held Women’s Tribunal Malaysia: Reimagining Justice.

The first of its kind, the tribunal, which provided a platform to present 26 cases that covered a wide range of issues facing women in the country — from poor or nil access to healthcare in rural areas to cracks in citizenship rights and inequality in the economic, social spheres –, sought to provide justice where conventional court hearings might not or could not have done so.

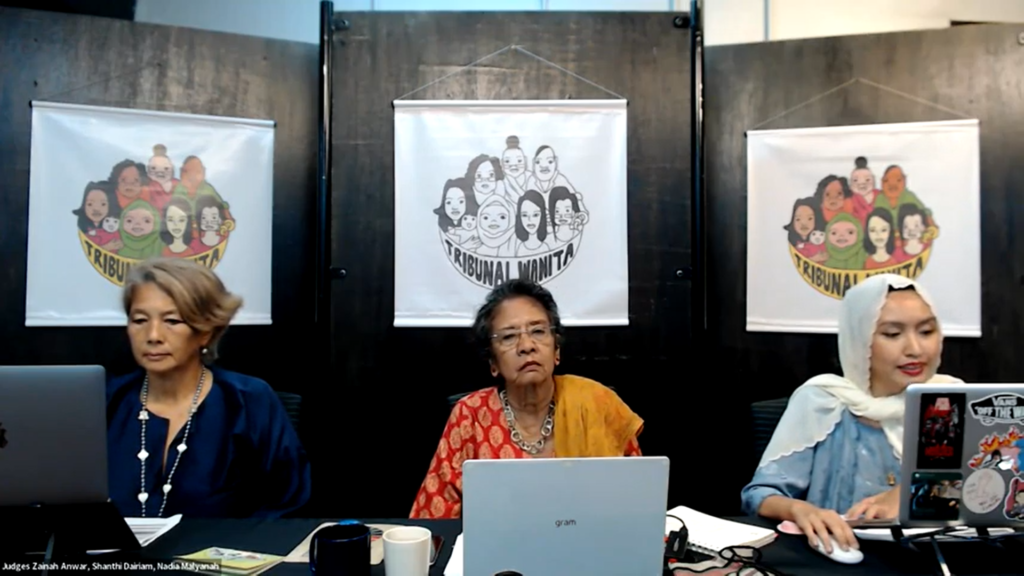

Three judges, namely Founding Director of IWRAW Asia Pacific Mary Shanthi Dairiam, Co-Founder of Sisters in Islam Zainah Anwar and Programme Associate at UNDI18 Nadiah Malyanah heard the cases in their entirety over a two-day period, before delivering their findings and recommendations towards reparation, strengthening of existing laws to counter the sufferings these women have endured.

The delay in the new Hospital Lawas, which was initiated in 1996, and which should have been completed by now to provide the much needed medical and health care facilities in the Sarawak town, was among the evidences of healthcare neglect raised in the cases brought up by Agnes Padan and Mebpung Akup.

The two women who live in the rural areas of Sarawak were witnesses at the tribunal who gave their testimonials on how their lives had been affected due to lack of access to emergency medical services or poor access to healthcare for them and their families.

Agnes Padan is the daughter of Kam Agong, a woman who died following complications after giving birth at the Lawas hospital. She could have been saved if she had timely access to emergency medical services.

Nearly 20 years after her death, there continues to be no trained obstetric and gynaecology specialist at Lawas Hospital and high-risk pregnancies and patients requiring caesarean section are referred to Miri General Hospital or Likas Women and Children’s Hospital, said Judge Malyanah who related the findings of the case healthcare for women in rural areas of Sarawak.

The state had failed the people of Lawas who have been waiting more than 24 years for a new hospital facility after being promised one in 1996 under the 7th Malaysia plan. This project has been identified as one of the worst ‘sick hospital’ projects in the history of Malaysia, with 3 collapsed hospital tenders worth hundred million ringgit each. More recently, a total of RM175 million has been allocated a third time to build a new 74-bed hospital, which is slated for completion by August 2023.

Mepbung meanwhile has been unable to access diagnostic work up and care for a suspected breast cancer as she does not have a Malaysian identity card.

This is a result of a larger systemic failure by the state to recognise the citizenship rights of indigenous children born in Sarawak, said Malyanah.

On the poor development of the healthcare system in Sarawak, Malyanah spoke of how the long distance and hours of travelling required to go to major hospitals in towns or even clinics for women from long houses and settlements in the rural areas of Sarawak had complicated medical treatment.

Travelling long hours just to reach hospitals in the towns of Sarawak for their medical and emergency needs or not having an oncologist in their town to take care of their specific health situation had directly impacted the lives of rural women in Sarawak.

Adding to this is the large discrepancy in the doctor to population ratio for Sarawak, which is 1:892 compared to the 1:150 ratio in Klang Valley. Across Sarawak itself, there is a further large discrepancy as Kuching Division has a doctor-population ratio of 1:604 whereas the smaller divisions of Kapit and Mukah have a ratio of 1:1721 and 1:2,038 respectively.

Some villages are dependent on mobile clinics and the Flying Doctor Services, which are scheduled once every one to three months and this poses a problem in the event of an emergency and patients will still have to travel for hours in dangerous timber roads.

There is also a mobile boat clinic but it is highly dependent on weather conditions.

Only 143 are accessible by tar road with 21 clinics accessible by logging roads, 19 clinics accessible by river, and the rest dependent on a varying combination of river, air, plantation, and logging roads. Only 170 out 215 clinics have a 24-hour electricity supply and only 128 out of 215 of clinics have treated water supply.

The number of oncologists at 5 at Sarawak General Hospital in Kuching (SGH) is way below the recommended 24 for the state. This has made specialised healthcare for cancer currently insufficient and it is also inaccessible to the rural population.

With only one main cancer treatment facility for radiotherapy at SGH, patients from other parts of Sarawak travel hundreds of miles for their treatment in Kuching.

Limited access to emergency surgical services, expensive antenatal care for pregnant woment and postnatal services that involve long journeys to town centres, as well poverty induced malnutrition and poor participation by the indigenous women in healthcare were among the many other findings Judge Malyanah cited at the tribunal.

During the COVID-19 pandemic and restricted movement orders, maternal healthcare access in Lawas deteriorated further as transfers to Sabah across the state border became very challenging as have transfers to Miri across the Brunei-Miri border.

The provision of healthcare based on citizenship have left many women with unresolved citizenship issues without access to healthcare.

For some, the lack of awareness and their remote location have made it even more difficult and longer to resolve their citizenship issues and consequentially their access to healthcare.

Recommendations for a fair rural healthcare system

Other than the probe into the much needed Hospital Lawas, other short term (within a year) actions sought at the tribunal were:

- To conduct an urgent service evaluation and stakeholder analysis of the current state of maternal healthcare provision in rural settings in Sarawak and Sabah

- Repeal immediately the directive for public hospitals and cllinics to refer undocumented persons to the Immigration Department

- Ensure that all pregnant women and mothers in Sarawak and Sabah have access to adequate, safe and accessible antenatal and postnatal care and government healthcare clinics locally, regardless of citizenship status

Among the medium term (within three years) recommendations were building local health capacity by training more healthcare professionals including speciality doctors, nurses and midwives from indigenous communisties, robust data collection and analysis of healthcare outcomes for women in Sarawak and Sabah and regular healthcare education and awareness programmes.

Ivy Josiah, who headed the Women’s Tribunal project, said the details of the 26 cases, that included citizenship issues, the plight of transgender women, sexual harassment and intimidation, inequality at work, and their respective findings and recommendations are expected to be published early next year in the tribunal’s website:https://www.womenstribunalmalaysia.com/en#tribunal

The proceedings of the tribunal can be also viewed at the site’s YouTube channel.

–WE