by Dr Rahim Said

In a world already bursting with strange headlines, one particular bit of news last week quietly slipped under the radar — and it shouldn’t have.

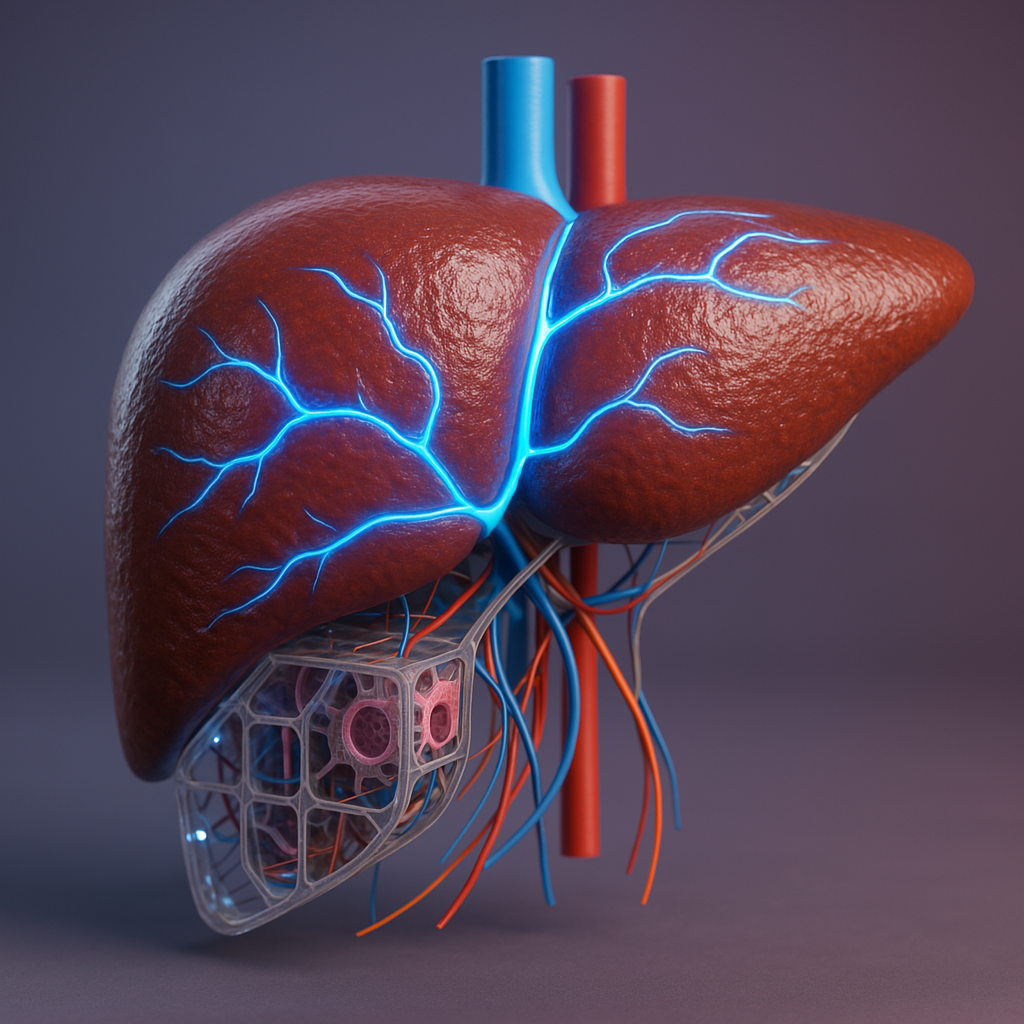

Japanese scientists have successfully kept a 3D-printed human liver alive for 30 days. Not just a blob of lab-grown tissue, mind you, but a functioning organ, processing toxins, producing proteins, and forming tiny blood vessels like it was born to do.

If that doesn’t make you pause between your “teh tarik” sips, it should.

For those waiting on transplant lists, this is nothing short of a miracle. Imagine a future where you no longer need to pray for a donor or hope someone else’s tragedy becomes your salvation.

You simply get a liver printed to order. No rejection, no endless waiting, no desperate appeals on social media. It’s the kind of science fiction stuff our grandparents could barely imagine while lining up at government clinics.

But like all great leaps in human history, this one comes with baggage. Because if we can print a liver today, why stop there?

Hearts, kidneys, maybe even a pair of lungs for those who stubbornly refuse to quit smoking. And eventually, entire limbs. Or entire people.

Which brings us to the age-old question: Just because we can, should we?

Philosopher-historian Yuval Noah Harari warned about this very thing in Homo Deus — a future where humanity begins to merge biology and technology, rewriting what it means to be human.

When organs can be printed and death delayed, mortality stops being a certainty and starts becoming a management issue. And you can bet your last ringgit it won’t be equally accessible to all.

Will these life-saving marvels be available for the average “mak cik” in Alor Setar or only the mega-rich and connected in Bukit Damansara?

Will life itself become yet another status symbol, like cars and watches, where those with means get to live longer, better, and stronger than the rest?

This Japanese achievement deserves applause. It could save lives, spare grief, and change medicine forever. But it also calls for serious, uncomfortable conversations about ethics, inequality, and whether we’re wise enough to handle the godlike tools we keep inventing.

Because one day, when death finally takes a holiday, we better make sure we know what to do with ourselves.

The views expressed here are entirely those of the writer

WE