Before we were sent off on our postings, the Ministry of Health sent us biochemists to the Institute of Medical Research (IMR) in Kuala Lumpur for “training.”

I don’t remember much of the training but I do recall being taken by a senior colleague to the best “chap fan” (mixed rice) restaurant located east of Suez. It was along Jalan Pahang and the trick was to get there before 12.30pm, after which the hospital’s hungry hordes laid waste to its spread.

After three months, we were dispatched to the front-lines. I got Perak.

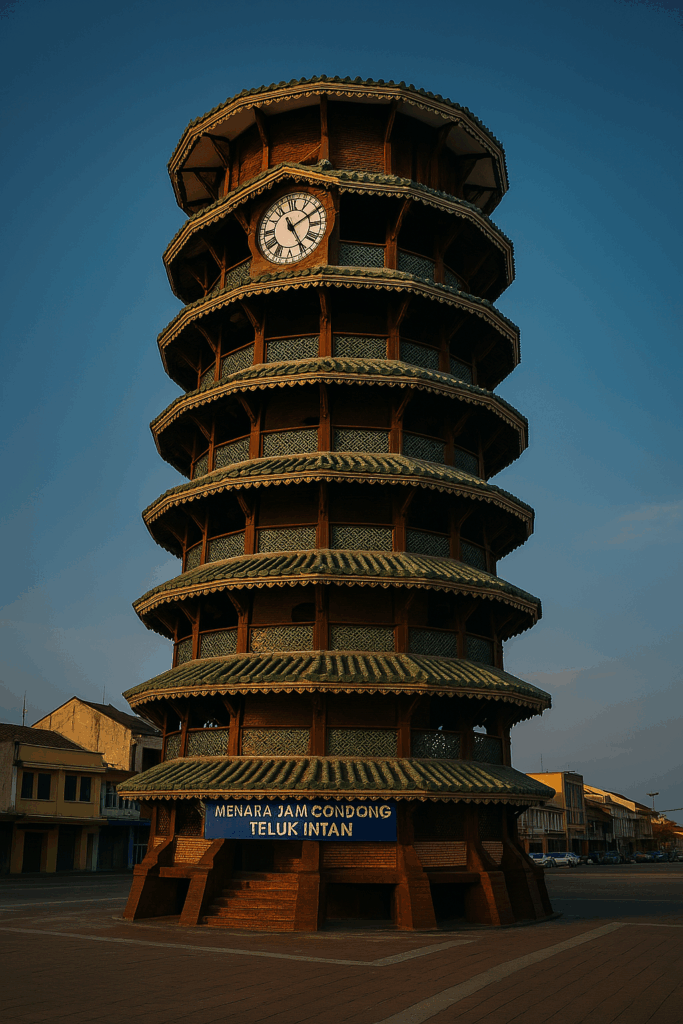

I reported to the state’s Chief Medical and Health Officer, a suave Sikh, who informed me that The Plan – he liked to Declaim in Capitals – was to send me to Teluk Anson (now Teluk Intan). No one had heard of Teluk Intan, not even Intan herself.

The prospect filled me with alarm as the place was only a district hospital with a rudimentary laboratory.

Sensing my unease, the CM&HO suavely slid in this caveat: “Pending your transfer, you’ll serve in Ipoh General Hospital.”

It was 1980 and the government wasn’t computerised so I wandered around in abject poverty for three months! Then my file reached whoever it was supposed to reach and I was deemed salary-worthy. My first salary came in a rush, all three months of it. (In the IMR, we only received an allowance).

Apart from the blood bank, the biochemistry department was the largest component of the pathology department. In Ipoh, we had two labs. There were smaller labs for hematology (bloodwork including the preparation of slides for biopsies) and serology (tests on serum).

You might see how a young man might rapidly get disenchanted amid such cheerful company first thing in the morning, three years in a row. But that’s another story.

At the time, medical lab work was primitive. Only the blood gas machine was automated. Everything else was done manually. Hundreds of titrations a day and it had to be reasonably accurate because the results mattered.

There were two of us and we needed to know the basic work as well in case of emergency. Nowadays almost all blood tests are automated. Back then, it could be soul destroying.

I had great admiration for some of the medical lab technicians (MLTs): they performed very skilled work rapidly and uncomplainingly despite not being paid much.

Most of them depended on overtime (OT) pay: someone had to man the labs on weekends.

When I joined, Mrs Ang, the senior biochemist, immediately told me to take over the OT assignations.

I quickly realised why. Many of the MLTs, who depended on OT, were highly suspicious of whoever doled it out. Try as I might I couldn’t convince some people of my scrupulous neutrality.

You can only be a good guy for so long. One day, I lost my temper and I threatened to transfer a constantly grumbling staffer to Teluk Anson.

I had no such power but he didn’t know it. Neither did anyone else because no one ever questioned my methods again. Even Mrs Ang gave me an approving nod.

I think it was then that she went to bat for me and I got off Telok Anson’s hook.

(The views expressed here are of the writer himself)