by Yong Soo Heong

In the aftermath of the May 13 1969 riots, the 1975 World Cup Hockey Tournament, held mostly in Kuala Lumpur, proved to be an unexpected catalyst for national reconciliation.

The unifying power of sports came to the rescue of a nation that was still healing from the wounds of divisiveness when the Malaysian Hockey Federation took on a last-minute request to hold the tournament after India pulled out as hosts. The MHF and the government machinery put everything together in one year, symbolising the strong dedication of our sports officials and administrators.

The year 1975 was a year when the nation stood still for hockey. And L-shaped tree branches all over the country were somewhat in short supply when they were cut, shaped and sandpapered to produce make-shift hockey sticks!

Edi Norsam, then a young boy staying in a Felda settlement in Sg Koyan, some 40km from Raub, Pahang remembers the hockey “fever” very well although it took place some 50 years ago.

The “fever” meant that any tree branch with an “L”-shaped outgrowth in his village would be hacked and sandpapered for makeshift hockey sticks as RTM sportscaster Rahim Razali captivated many a young boy’s imagination with his coverage.

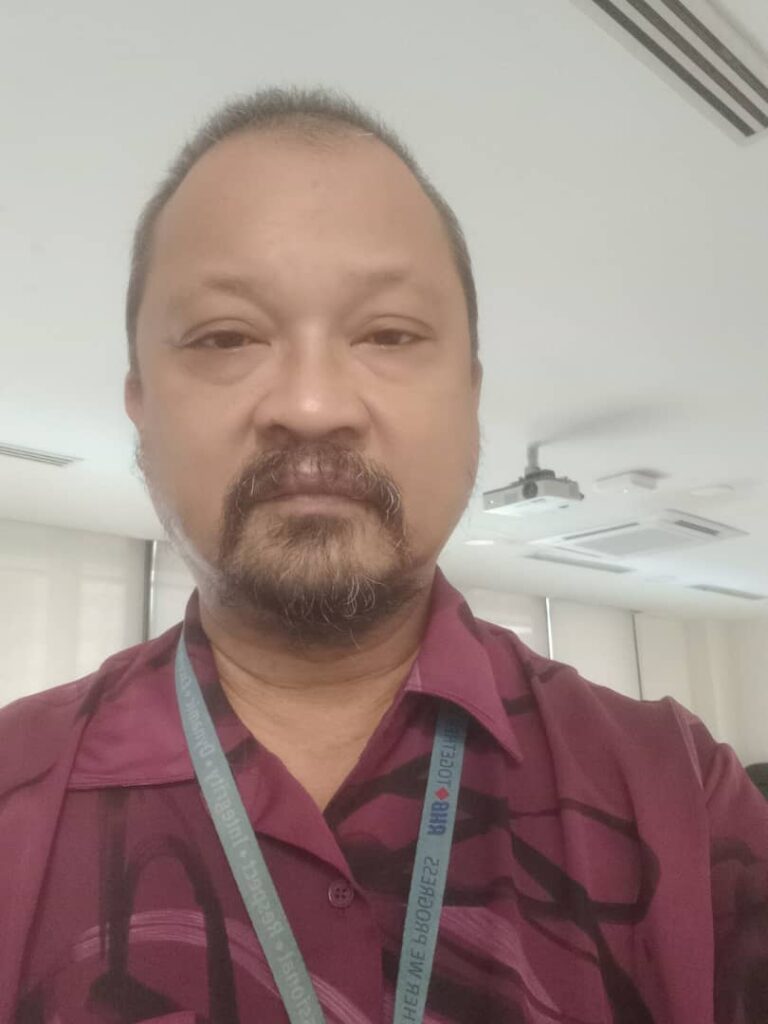

Edi Norsam 50 years later

“The young boys who played with makeshift sticks had new heroes. Thank you, Poon Fook Loke, Sri Shan and Khairuddin Zainal — you are in our hearts. The World Cup in 1975 will always be remembered, along with the rain, mud and waterlogged pitches,” said Edi.

Like Edi, Saodi Mat Atar was another L-shaped tree branch hacker. He was in Std 5 at the time and was taken up by the sport. This was reinforced by his class teacher, Cikgu Yunus, who brought his tv set to school in Bagan Datuk, Perak, for the class to follow the hockey matches.

And of course, Saodi went for the best there was, the jambu (guava) tree, known for its hardness!

Thirumamani Sundaraj, currently the principal of St. Xavier’s Institution in Penang, remembers watching the matches with his dad from a black-and-white TV set back then. “A black and white memory,” he recalls as Malaysia rose to the pinnacle of world hockey.

George Das, ex-sportswriter with The Star and New Straits Times, besides being impressed with the prowess shown by the Malaysian hockey team in that tournament, was also fascinated by the school students who went autograph-hunting or greeted the players off the field.

One of them was Yon Z, then a Form 2 student at the Raja Perempuan Secondary School in Ipoh, who subsequently rose in the field of education. “Had a crush on those handsome hockey players from Spain,” she remembers.

The national hockey team’s crucial role in 1975 was amply acknowledged recently at the 9th edition of Sports Flame, a gathering of local sporting greats graced by the Sultan of Pahang, Sultan Abdullah Ri’ayatuddin Al-Mustafa Billah Shah.

The royal event was a testimony to the special tribute given to the hockey players for their gritty display 50 years on and was specially organised by George Das, Fauzi Omar, Lazarus Rokk, Johnson Fernandez and Chris Raj.

Lazarus, the “evergreen” Master of Ceremonies at the Sports Flame event, was almost choked with emotion when he recalled the emotional spark that rekindled national unity which arrived with the hockey tournament as Malaysians rallied behind the national team with a common cause, transcending race and religion.

Hosting the World Cup was a statement of Malaysia’s growing presence in international hockey. As the tournament unfolded, it was more than a quest for glory—it became a national rallying point. It wasn’t about medals; it was about identity and belonging. It was Malaysia, standing tall on the world stage.

The electrified home crowd, a colossal melting pot of Malaysians, buried the horrors of 1969 in a blur of collective euphoria. It was a sight to behold when many Malaysians hugged one another, most of them total strangers.

Malaysia’s dramatic victory over the reigning champions, the Netherlands, in the group stages ignited national pride. Streets erupted in celebration, and ethnic differences momentarily disappeared in the shared triumph. After the winning goal was scored before the match ended at the Kilat Club in Kuala Lumpur, spectators invaded the pitch and someone even snatched away the hockey stick of skipper N. Sri Shanmuganathan before it was brought back for the game to resume.

Even in the semi-finals at Stadium Merdeka, when Malaysia narrowly lost to India—the eventual champions—the passion and unity displayed showed that it wasn’t about medals; it was about identity and belonging.

N. Sri Shanmuganathan today

Sri Shan said:” We played as brothers. Malays, Chinese and Indians showed what Malaysian unity was in 1975. We showed no fear. All we wanted was to bring glory to our beloved country, Malaysia.”

Forward M. Mahendran remembered how motivational guru Datuk Lawrence Chan instilled nationalistic fervour in the players. “In a darkened room, he called out our names for us to stand up, then lit a candle. Behind the glow stood the Malaysian flag, and the strains of ‘Negara Ku’ stirred our spirits. That moment remains unforgettable.”

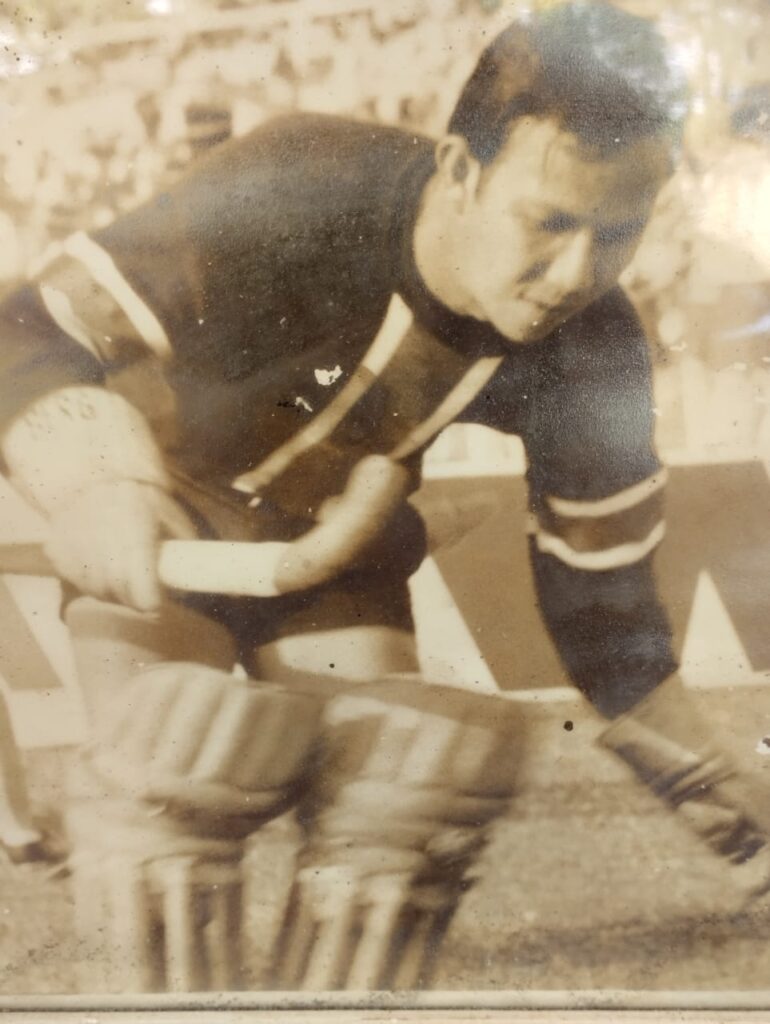

Goalkeeper Khairuddin Zainal still recalls his post-match tears: “Each time I look at the photo of me crying after our loss, memories flood back. Fifty years on, the weight of our journey, the hopes of a nation, and the agony of coming so close still linger. But we stood among the world’s best.”

A young Khairuddin Zainal

Striker Franco D’Cruz, who also had an improvised hockey stick carved from a jambu (guava) tree when he was seven years old, emphasised that though Malaysia didn’t get a podium finish, the 16 players won something greater—“We won the hearts of the nation.”

Franco D’Cruz and team mate Brian Sta Maria

Often seen as just entertainment, sports hold a unique ability to unite people beyond politics and policies. The echoes of a stadium, the shared dreams of a nation, and the triumph of beating the odds can create a bond stronger than any government decree. Malaysia’s historic 1975 campaign was more than a game—it was a testament to how national pride can overcome differences.

Although unity remains a constant challenge, the lessons of 1975 still resonate today: True togetherness is forged through shared experiences, and few things bring people together like the collective passion for sports.

Looking ahead, Malaysia must recognise that investing in sports is more than just training athletes. It strengthens national identity, fosters pride, and reinforces the belief that Malaysia thrives best when united.

The heroic 16 of 1975: N. Sri Shanmuganathan, Khairuddin Zainal, Brian Sta Maria, Wong Choon Hin, K. Balasingam, R. Rama Krishnan, Len Oliveiro, N. Palanisamy, Poon Fook Loke, Franco D’Cruz, R. Pathmarajah, M. Mahendran, Mohd Azraai Zain, A. Francis, Phang Poh Meng, and S. Balasingam. Coaches: Ho Koh Chye, R. Yogeswaran, and Lawrence Van Huizen.

WE